Deciding how to handle the death of a player character is something that every Dungeons and Dragons DM must face. Unfortunately, the game mechanics as written have always struggled to give characters the meaningful, evocative end that heroic characters deserve. In this article, we’ll take a look at character deaths in Dungeons and Dragons.

The Evolution of Character Deaths in D&D

Over the years, Dungeons and Dragons has presented varying mechanics to handle the death of a player character.

Let’s explore the various evolutions:

Death at 0

In the earliest editions of the game, characters died instantly when they were reduced to 0 hit points, with no extra time to do anything.

Although considered harsh by modern game design principles, death at zero was the norm in both TTRPG and videogame design of the late 70s and early 80s (just look at Super Mario Bros for the NES, where a single touch from an enemy can end send Mario the Great Green Pipe In The Sky).

And it does have it’s benefits! When a single false step onto a dungeon trap or a blow from an orc’s spear can end a character, it really heightens the stakes of an adventure. Players tend to stray towards caution, and this method can actually encourage roleplaying and creative thinking, because leaping into combat is often the riskiest choice.

Unfortunately, a clear problem developed — when combat did happen, characters couldn’t easily have the “heroic last stand” moment that appeared in so much of the source literature that inspired Dungeons and Dragons, and Death at 0 systems tended to turn into meat grinders, prompting some frustrated players to create endless clones of the same character to try to get through a trap-filled dungeon.

Death at -10

Later revisions of the Dungeons and Dragons rules allowed characters to remain in an unconscious, dying state until -10 hit points, with most systems incorporating a caveat for massive damage that could still result in an instant kill.

One or two of these systems even allowed characters to act during while at negative health, whether through a variant rule or, as in Dungeons and Dragons 3.5, through feats or abilities that characters could obtain.

Many players considered this to be an improvement over Death at 0 systems, as it allowed your party members to (hopefully) rescue you from certain death if they could get to you in time.

The downside? Spending 4 rounds unconscious and unable to do anything because a kobold got a crit with a crossbow just SUCKS as a player.

It’s boring having nothing to do on your turn of combat, and if your character is unconscious, you’re just stuck twiddling your thumbs until your allies either manage to heal you or run screaming away to leave you to your doom.

5e-style Death Saves

In 5th edition Dungeons and Dragons, characters fall unconscious below 0 hit points, just like they do in Death at -10 systems. What changes is what you can do while you’re unconscious, by introducing a special saving throw the player can roll each turn.

Death Saving Throws

Whenever you start your turn with 0 Hit Points, you must make a Death Saving Throw to determine whether you creep closer to death or hang on to life. Unlike other saving throws, this one isn’t tied to an ability score. You’re in the hands of fate now.

Three Successes/Failures. Roll 1d20. If the roll is 10 or higher, you succeed. Otherwise, you fail. A success or failure has no effect by itself. On your third success, you become Stable. On your third failure, you die.

The successes and failures don’t need to be consecutive; keep track of both until you collect three of a kind. The number of both is reset to zero when you regain any Hit Points or become Stable.

Rolling a 1 or 20. When you roll a 1 on the d20 for a Death Saving Throw, you suffer two failures. If you roll a 20 on the d20, you regain 1 Hit Point.

Damage at 0 Hit Points. If you take any damage while you have 0 Hit Points, you suffer a Death Saving Throw failure. If the damage is from a Critical Hit, you suffer two failures instead. If the damage equals or exceeds your Hit Point maximum, you die.

On their own, Death Saves greatly improve the experience of the beleaguered player, simply because it gives them a high-stakes roll they can make each turn…at least until you Stabilize.

From that point on, it has the same problem as Death at -10, where the unconscious player is just stuck doing nothing each turn.

Building Heroic Deaths Into D&D 5e Death Saves

The Bearded Halfling has recently launched a YouTube channel, and his first video drops a couple of interesting house rules on how to add tension to death saves in D&D 5e.

Give it a watch:

To summarize, the small bearded man suggests three changes:

- The Boromir Rule, allowing characters to auto-fail a death save to perform a limited set of actions when they hit 0 HP.

- Lingering Death Saves, which make failed death saves persist until the character’s next long rest.

- Death Dice, in which the DM rolls death saving throws for PCs and keeps the result hidden (and uses some nice chunky dice specifically for that purpose)

As a fellow beard-haver, I think these are really cool ideas! I’m not going to delve too deeply into the second two, but I want to visit the Boromir Rule in greater depth.

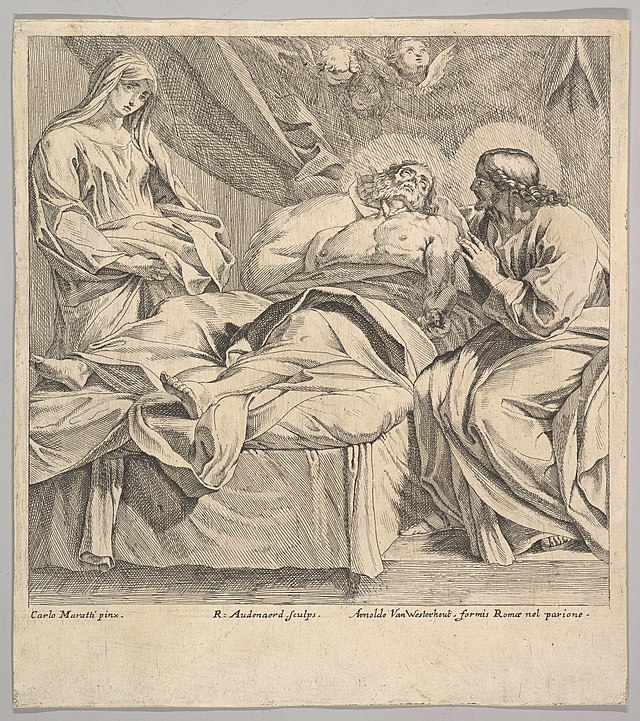

Boromir’s End, the Quintessential Heroic Death

I’m not sure if there is a cinematic death in a fantasy movie more gripping than Boromir’s end in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, so the Boromir Rule is aptly named.

In the scene, Boromir, son of Gondor, leaps to the defense of the hobbits Merry and Pippin. He is alone, facing a horde of orcs, and the horn of Gondor cries out in the forest.

We see the Uruk-hai captain rise the hill, level his bow, and cast an arrow straight into Boromir’s heart.

The viewer knows it is a mortal blow.

There’s no recovery from a wound like that.

Boromir is dead already.

He falls to his knees…

…and rises once more, crying out as he drives his sword into another orc. He see him fell two orcs before the second arrow hits.

Again, Boromir falls.

Again, he struggles to his feet and fells three more of his foes.

We don’t even see the third arrow, only hear it as it pierces Boromir’s broken body.

With the last arrow, Boromir finally falls, and even then, we are able to view his final conversation and reconciliation with Aragorn before he passes.

Incidentally, if you’ve never listened to Karliene’s Lament for Boromir, do yourself a favor and listen while you read the rest of this article.

Contrast Boromir’s end with what often happens in D&D:

DM Bob: “Okay, Fred, the orc’s arrow hits you in the chest, dealing 12 damage.”

Fred: “Bummer. I’m a -3 HP.”

DM Bob: “Oof. Bad luck, you’re unconscious. On your next turn you’ll need to roll a death save.”

*next turn*

Fred: “Crap. I fail.”

DM Bob: “Okay, that’s all you can do this turn. You can try again next turn.”

B O R I N G

The Bearded Halfling’s Boromir Rule gives your game table the opportunity to feel and experience these heroic character deaths:

- Though bloodied and broken, a paladin raises his shield and places himself within the path of the ravening monsters, holding them off long enough for the rest of the party to escape.

- A wizard uses her dying breath to seal away a powerful demon, using her dying breath to fuel the ritual and whisper the final words of the incantation.

- Though poisoned and stumbling, the rogue manages to use his final moments to toss an evil artifact into the flames, destroying it forever.

- Seared beyond saving by the flames, a barbarian roars in rage and holds up the burning central beam of a collapsing house to rescue villagers trapped within.

Other ways to give characters deaths more impact

Of course, The Bearded Halfling’s Boromir Rule isn’t the only way to handle a situation where a character is actively dying but still able to act.

Other authors have written similar rules, but I like the Boromir Rule because of its simplicity.

But what if you don’t want to implement a new house rule, but you still want to increase the narrative impact of character deaths?

Here’s one simple trick I’ve used at my own tables:

Every time a character makes a death save, prompt the player with a roleplaying question. Here are some examples:

- “In what may be your final moments, what person do you find yourself thinking of? What do you wish you could say to them?”

- “As you stray nearer to death, what memory flashes before your eyes?”

- “Your life may soon come to a close. Do you have any regrets?”

- (For a cleric) “Your life of devotion draws to the end. Do you offer any final prayer to your goddess before your body collapses?”

- (For a warlock) “Your vision turns red as death looms close. What curse do you place upon the foes who have orchestrated your end?”

This simple prompt allows you to bring more narrative flair and meaning into the impending death of character, even if you don’t implement any changes to the core rules D&D 5e uses to handle death saving throws.

Character deaths in other systems

Of course, the way D&D handles character death isn’t the only option, and I think D&D DMs can learn a lot from exploring other TTRPG systems.

I reached out to my followers on Bluesky to see how other systems handle character death and if any of them include mechanics that better support narrative deaths for characters.

Some systems offer direct mechanical ways for characters to sacrifice themselves for the rest of the group:

Some games lean into the opposite, where characters are intentionally expendable:

Tom Fenny dropped my favorite reply (which couldn’t be embedded for some reason):

Cthulhu Dark remains a favorite ironically because it’s vague.

Perfect for a mysterious lovecraftian mystery. When your sanity hits zero you sort of just… disappear in a way that suits the player but renders you no longer capable of progressing.That could be death, or it could be something else.

I’m fascinated by the idea of “death” in a game’s mechanical sense meaning the character becomes unplayable rather than literally dead.

It opens up so many possibilities for the DM to feature character as an NPC in some sense in the future.

Games With Built-In Boromir Rules

I’ve been closely watching the development of Starlight Journals by Captain Zenscuel, a far-future sci-fi TTRPG that has a lot of crunch and complexity.

I’ve had the opportunity to sit in on a couple of Zenscuel’s playtests and I think it’s going to be a game that will appeal strongly to players who enjoy tactical, wargame-style combat.

In Starlight Journals, characters have Health, Stamina, and Resolve+Nerve. If any of these reach 0, the character will begin taking injuries, which lower your stats.

Injuries also deal Critical damage, and death only happens when your Critical value is expended.

This seems to turn death into a sort of slow burn, where characters are still able to function (albeit with diminished capacity) as they stray closer and closer to death, until their body finally gives out.

Over time, this builds a lot of tension during the session, as the player and the rest of the party face a building dread about the fate of the wounded hero.

It also allows the player to decide how to handle their character’s death: do they flee and try to heal? Or do they embrace their character’s death and go out in the blaze of glory?

You can read more about Starlight Journals here.

Rituals of the End

The loss of a player character, particularly one that has been part of a long-running campaign from the beginning, is a profound moment for a player and their game table. In my opinion, its one that deserves more weight than just “lol, better roll up a new character.”

House rules and roleplaying prompts aren’t the only way to enhance character deaths in your campaign — out of character elements can also add to the experience.

In closing, here are some small traditions I’ve used in various gaming groups to remember fallen characters:

- After a character passes, go around the table and ask each player to share one of their favorite memories about the fallen character.

- Start each session with the players offering a Toast to the Fallen with their drink of choice.

- Place the character’s miniature on a shelf in a place of remembrance over the game table.

- Pin the character’s sheet to a bulletin board in your game room, serving as a Wall of the Honored Dead.